Alleviation: An International Journal of Nutrition, Gender & Social Development, ISSN 2348-9340 Volume 1, Number 1 (2014), pp. 1 - 8

© Arya PG College, Panipat & Business Press India Publication, Delhi

www.aryapgcollege.com

Gender Responsive Budgeting – Initiatives and Challenges

Anjali Dewan

Head, Department of Home Science

St. Bede’s College, Shimla (Himachal Pradesh)

Email: dewananjali@rediffmail.com

Introduction

It is unfortunate but almost half the population of India after sixty years of independence and promise of equality is still neglected. The social indicators such as education, health reveal a poor picture of women in India. The sex ratio is unfavorable with a large number of women suffering from malnutrition and anemia. The political participation of women, representation in decision making bodies is lesser than that of men. More women are poor and their number in sex trade and human trafficking is beyond imagination. The 73rd and 74th Constitutional amendment Act has changed the situation in politics by enforcing 33 per cent reservation of seats for them in the local bodies. Unfortunately, the Women’s Reservation Bill is still waiting to be accepted in the Parliament. Under these adverse circumstances, there is a need for gender Mainstreaming with Gender Budgeting as a means of incorporating a gender perspective at all levels of the budgetary process.

The need for gender budgeting arises from the fact that the National Budgets have an impact on the various sections of the society. This is through the pattern of resource allocation, the directions of the Fiscal and Monetary policies, the measures taken for resource mobilization, the actions for the under privileged sections of the society. Women stand apart as the vulnerable section of the society. Thus there is a need to formulate a gender responsive budget which can contribute to achieving of the objectives of gender equality, human development and economic efficiency. This exercise facilitates the increase in accountability, transparency and participation of the women. The macro policies of the government can induce a significant impact on gender gaps in the various micro indicators related to health, education, income etc. Gender mainstreaming requires gender responsive policy. When gender equality considerations become a part of the policy making, the concerns of both men and women become an integral part of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the policies which affect all the sections of the society.

Gender budgeting does not mean a separate budget for women. It encompasses the entire budget consisting of revenues as well as expenditures. It involves all the stages of the budgetary process and implies gender sensitive analysis, assessment and restructuring of the budget if needed. If the gap between policy and resource allocation is to be filled, then budget making and policy making must be carried out in close collaboration.

Policies and Programmes: A Brief Review of the Five Year Plans

First Five Year Plan (1951-1956)

The programmes for the development of women were mainly welfare oriented. The Central Social Welfare Board was set up in 1953 to promote the welfare of women through agencies like voluntary organizations and charitable trusts etc. The Board, thus, adopted welfare measures through the voluntary sector.

Second Five Year Plan (1956-1961)

During this plan, the Mahila Mandals were set up and the women were organized in these mandals with the cooperation and support of the state to act as focal points at the grassroots levels.

Third, Fourth and Other Interim Plans (1961-1974)

In these plans, the priority was given to the education of women. Measures were undertaken to improve maternal and child health services. The plan supported economic development, employment and training for women as the focal points for their socio-economic lift.

Fifth Five Year Plan (1975-1980)

marked shift in the approach for women was made in this plan. The object of shift in approach was to integrate welfare and development, employment and training for women as the focal points for their socio-economic lift.

Sixth Five Year Plan (1980-1985)

This plan was a landmark in the history of women’s development issues. It included for the first time, a separate chapter on women’s development. It recognized women as a separate target group and accorded them a rightful place in the developmental planning. The plan adopted a multi-disciplinary approach, with a thrust on education, employment and health to inculcate confidence and to generate awareness among them to recognize their own potential. The family was recognized as the unit of development and women being an important member of this unit were given special attention.

Seventh Five year Plan (1985-1990)

The main objective of this plan was to raise the economic and social status of women and to bring them into the mainstream of national development. Thus, the multi-disciplinary approach which stared in the Sixth Five Year Plan continued in this plan too. Efforts were made to inculcate confidence among women and to bring about an awareness of their own potential for development, their rights and privileges.

Eighth Five Year Plan (1991-1996)

The approach of this plan underwent a major change. It shifted from women’s development to women empowerment. This plan ensured a flow of benefits to women in the core sectors of education, health and employment. This plan for the first time had a gender perspective. It stressed the need for a definite flow of funds from the general developmental sectors to women. The plan document made a special mention to the women stating that ‘the benefits to the development from different sectors should not bypass women and special programmes on women should complement the general development programmes. The latter, in turn, should reflect great gender sensitivity.

Ninth Five Year Plan (1997-2002)

This plan called for the empowerment of women and aimed at convergence of the existing services which were available in women specific and women related sectors. It directed the Centre as well as the State governments to adopt special strategy for ‘Women Component Plan’ through which not less than 30 per cent of the funds were expected to be used for women from all the general developing sectors. The plan also advocated a special vigil on the flow of the funds to bring forth a holistic approach towards empowering women.

Tenth Five Year Plan (2002-2007)

The plan accorded a complementary role to the Women’s Component Plan. It ensured gender budgeting, so that women get their rightful share in development. It stressed the implementation of the National Policy for the Empowerment of Women 2001 through equal access in the political, economic and social life and mainstreaming of gender perspective into the development process.

New Eleventh Five Year Plan (2008-2113)

The govt. has constituted a committee of feminist economists to ensure gender sensitive allocation of public resources. The 21 member committee includes Renna Jhabvala of SEWA, Jean Dreeze and Bina Agarwal.

Objectives of Gender Budgeting

Gender Equality

The primary objective of the gender budgeting refers to the budgets and related policies with a view to promote gender equality as an integral part of the human rights. Gender budgeting makes the gender specific effects of the budgets visible and raises awareness about discrimination against women. It is regarded as a core strategy for understanding the gender impacts of the budgets and policies.

Accountability

Gender budgeting is a crucial tool for monitoring gender mainstreaming activities as the public budgets involve all policy areas. It is a mechanism for establishing whether a government’s gender equality commitments are translated into budgetary commitments. It makes governments accountable for gender policy commitments.

Transparency and Participation

Gender budgeting increases the transparency of and participation in the budget process. It aims at democratizing the budgetary processes as well as the budget policy in general. Gender responsive budget initiatives can contribute to the growing practice of public consultation on and participation in the preparation of budgets, in monitoring their outcomes and impact particularly ensuring that women are not excluded from this process. This strengthens the economic and financial governance by promoting transparency.

Efficiency and Effectiveness

Gender budgeting contributes to a better targeting of policy measures and in the pursuit of effectiveness and efficiency. To reach the political goals and raise the scarce resources effectively and efficiently, governments should take into consideration that women and men due to their unequal social positions and ascribed social roles, might have different needs and that they may react differently to apparently gender-neutral measures. Gender budgeting ensures this specific gender awareness and is an important step towards good economic governance.

Good Governance

As gender inequalities lead to major losses in social cohesion, economic efficiency and human development, gender budgeting can be regarded as an important strategy in pursuit of equal citizenship and a fair distribution of resources. It is a tool for strengthening good economic and financial governance.

Analysis of the Union Budgets

analysis of the central budgets reveals the extent to which the aspects of gender budgeting have been taken into account. The public expenditure was categorized into three classes:

• Expenditures on programmes specifically targeted to women and girls.

• Pro-women allocations.

• Mainstream expenditure.

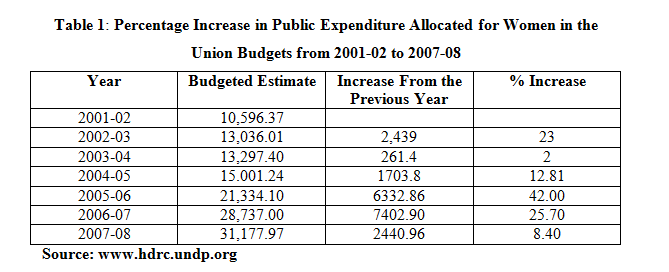

The trend shows an increase in the public expenditure allocated for women in the Union Budgets from 2001-02 to 2007-08.

Challenges in Gender Budgeting

There have been obstacles in terms of lack of data or appropriate tools and expertise or they may be based on resistance or lack of will and commitment at the political level or in the administration. These challenges can only be met through constant political pressure and compliance with the international commitments. Active steps must be taken to have gender budgeting recognized as a priority. A recent research in economic theory, budget making and gender equality demonstrated the role played by economic theory in the development of economic policy and the consequent budget making. New thinking needs to be developed to evaluate the economic theory and to find ways to accommodate the principles inherent in the theory while rendering it neutral in terms of its potential discriminatory effects. The dialogue between economists and gender experts should be encouraged and promoted. There is an urgent need to make sure that gender budgeting is introduced within an overall strategic process and at a level that can be developed. Until and unless the policy makers and budget makers are doing gender mainstreaming and gender budgeting, change will not happen where it should most effectively happen

Conclusions

Gender budgeting requires the mechanisms, guidelines, data and indicators to enable those who are formulating budgets as well as monitoring and evaluating them. This will help them in keeping track of the fulfillment of the objectives of the budget. This can be made possible only through the creation of a long term gender sensitive macro policy environment conducive for ensuring the empowerment of women. It calls for capacity building and gender sensitizing of women’s political representatives, creating awareness and understanding of the fact that budgets affect men and women differently. This is due to different social and economic positioning and thus affecting the budgetary allocations. The 73rd and 74th Amendments of the Constitution of India which mandates for one third seats for women is a landmark for inculcating confidence, promoting leadership qualities and participation in the economic decision making. The passing of Women’s reservation Bill in the Parliament which is long overdue will further elevate their socio-economic life. If we want women to have their rightful share of the budget, there is a need to have committed politicians, government administrators, a distinctive civil society and a gender sensitive media. Once the momentum is achieved, women will find themselves on a higher platform. Gender budgeting has to be built up within the macro-economic framework.

References

Aggarwal RK (2007) Gender Budgeting: Initiatives in India. Vikas Vani Journal 1(3) 26-33.

Banerjee N and Maithreyi K (2004) Sieving Budgets for Gender. Economic and Political Weekly October 30.

Government of India (1974) Report of the Committee on the Status of Women. New Delhi: Government of India.

Kekre KP (2007) Gender Equality with Gender Responsive Budgeting. Vikas Vani Journal 1(3): 34-42.

Lahiri A, Chakraborty L and Bhattacharya PN (2001) Gender Budgeting in India: Post Budget Assessment Report, NIPFP.

Planning Commission (2001) Report of the Steering Committee on Empowerment of Women and Development of Children for the Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-2007). New Delhi: Government of India.

Planning Commission (2006) Towards Faster and More Inclusive Growth, Approach to the 11th Five Year Plan by Planning Commission, New Delhi: Government of India.

www.hdrc.undp.org

www.Indiabudget.nic.in

www.Unifem.org