Alleviation: An International Journal of Nutrition, Gender & Social Development, ISSN 2348-9340 Volume 1, Number 1 (2014), pp. 1 - 8

© Arya PG College, Panipat & Business Press India Publication, Delhi

www.aryapgcollege.com

Organoleptic Evaluation and Retention of Vitamin C in Sprouted Pulses Incorporated Food Preparations

Tarvinderjeet Kaur

Associate Professor, Department of Home Science, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, Haryana

Email: tarvin_khushi@rediffmail.com

Introduction

In recent years, sprouts have become very popular among health conscious consumers due to their nutritional attributes. Sprouts are packed with a variety of high quality health maintaining important nutrients that are highly beneficial for all age groups. The potential protective role of sprouts and their active components especially vitamin C have been extensively studied and much of literature focuses upon healthy role of vitamin C. During recent years, importance of vitamin C has been realized in terms of its antioxidant and anti carcinogenic properties. Vitamin C is considered to be super drug which imparts to its users superior health, increased stamina, superior mental prowess, resistance to infection and the suppression of malignant diseases (Suzane et al 1991). Consumers are looking for variety in their diets and are aware of health benefits of value addition to foods with fresh fruits, vegetables, green herbs as well as sprouts from locally available sources. Generally, sprouts are consumed without any cooking involved but to add variety in the diets, seeds sprouts can be incorporated into different recipes. However because of effect of cooking on vitamin C content, the real nutritional value of cooking preparations is not equal to fresh ones. Studies on effect of cooking on vitamin C are available, but it is necessary to investigate further, the effect or compare the different domestic preparations on retention of vitamin C. Thus, the present study aims at incorporating sprouted pulses into commonly consumed food preparations and determining the retention of vitamin C in these developed preparations

Material and Methods

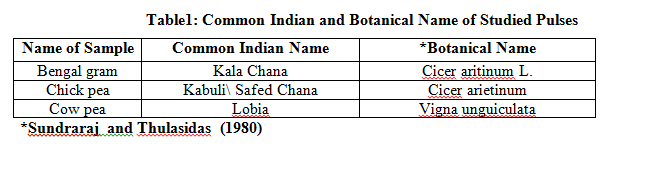

Three whole pulses namely bengal gram, chick pea and cow pea were selected for the present study because these are most popularly consumed by all the sections of the society in India (Table 1). The pulses under study were purchased in bulk from the local market of Kurukshetra (Haryana), India.

Processing of the Samples

All the three pulses were sorted, cleaned to remove the impurities and stored in an airtight plastic container for further use.

Sprouting

All the three pulses were sprouted by the standard method (Kaur 2009).

Development and Standardization of Food Preparations

The sprouted pulses were incorporated into cutlet, stuffed parantha, pulao, chat and dal curry applying different cooking methods viz. deep fat frying , shallow fat frying, boiling, steaming and pressure cooking (Kaur 2009). These methods of cooking were selected because they are the methods commonly used in Indian homes for cooking. For different preparations, different levels of incorporation i.e., between 15 - 50 per cent of sprouted pulses were tried. All the developed food preparations were organoleptically evaluated by a panel of twelve judges using nine point Hedonic Scale (1965).

Estimation of Vitamin C

The recipes adjudged best by the judges were selected for determining the retention of vitamin C. The vitamin C content of raw pulses, sprouted pulses and in different developed food preparations were determined by the standard method

Statistical Analysis

The data were subjected to statistical analysis using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0. ANOVA and Tukey HSD (Honestly significant difference) test were used to obtain the differences in organoleptic scores, within different level of incorporation of sprouted pulses in food preparations. Level of significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

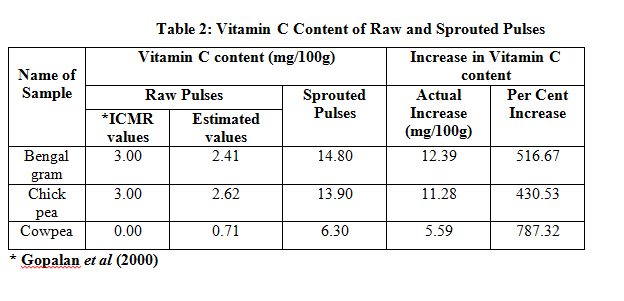

Estimation of Vitamin C in Raw Pulses

In the present study, vitamin C content of the selected raw pulses varied from 0.71(Cow pea) to 2.62 (Chick pea) mg per cent (Table 2). Results revealed less vitamin C content in bengal gram and chick peas whereas more in cowpeas than that reported by Gopalan et al (2000). The differences in vitamin C content may be attributed to the species (Kuti and Kuti 1999), variety of samples (Achinewhu and Hart 1994), season (Vanderslice and Higgs 1991), rainfall, manure used, different stages of maturity, storage method and length of storage (Nogueira et al 1978).

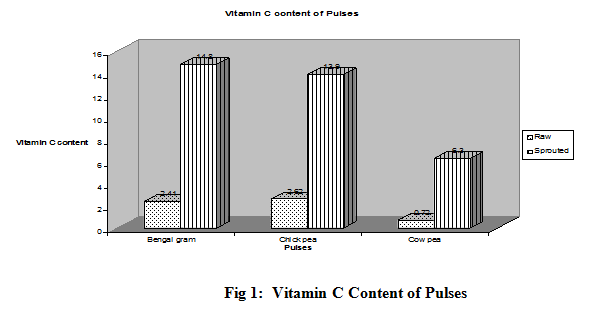

On sprouting, the vitamin C content of pulses increased significantly (P < 0.01), compared to raw values and varied from 6.30 (Cow pea) to 14.8 (Bengal gram) mg per cent (Fig 1). The per cent increase in vitamin C content was found to vary from 430.53

(Chick pea) to 787.32 (Cow peas). The findings of the present study are comparable with the reports of Chattopadhyay and Banerjee (1953), Badshah (1992) and Kavas and Nehir (1992).

Sensory Evaluation of Developed Food Preparations

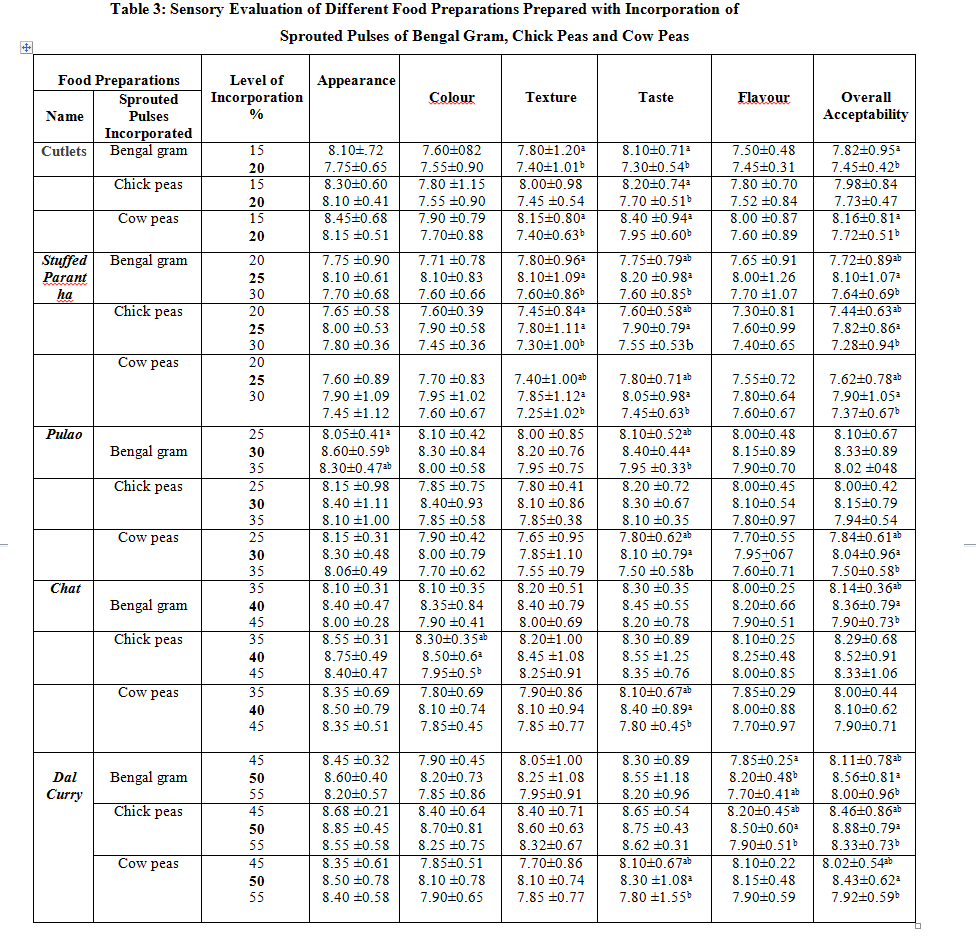

The sensory evaluation of the food preparations made with incorporation of sprouted pulses revealed that all the food products developed were organoleptically acceptable with incorporation of sprouted pulses from different sources but at different levels. It has also been noticed that when the level of incorporation of sprouted pulses increased or decreased beyond the accepted levels in any developed preparation, the mean scores for organoleptic evaluation for appearance, color, texture, taste, flavor and overall acceptability decreased (Table 3).

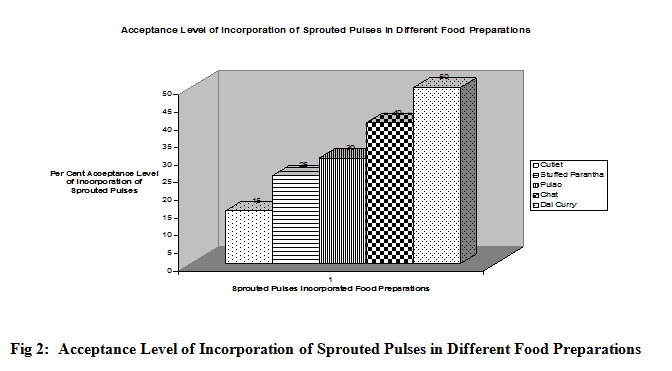

The most acceptable level of incorporation of sprouted pulses in different preparations varied from 15 to 50 per cent. Dal curry was most acceptable at 50 per cent level of incorporation and had the highest level amongst all the preparations, whereas, for cutlets, the best level of incorporation was minimum i.e. 15 per cent. Stuffed parantha, pulao and chat were best accepted at 25, 30 and 40 per cent level of incorporation, respectively (Fig. 2).

Analysis of data for organoleptic evaluation of the food preparations showed that the overall acceptability scores awarded by the panel of judges for dal curry were maximum among all the developed preparations and the respective scores for overall acceptability varied from 8.43±0.62 ( Cow peas dal curry) to 8.88±0.79 ( Chick peas dal curry). In dal curry, non-significant difference appeared within 45 per cent, 50 per cent and 55 per cent level of incorporation for appearance, color, texture and taste, while, significant difference (p < 0.05) was found for flavor and overall acceptability scores (Table 3). Multiple comparisons with Tukey HSD test further revealed significant difference (p < 0.05) for flavor and overall acceptability score within 50 per cent and 55 per cent level of incorporation in dal curry.

Sprouted stuffed parantha scored minimum overall acceptability scores which ranged from 7.82±0.86 (Chick peas stuffed parantha) to 8.10±1.07 (Bengal gram stuffed parantha). In stuffed parantha, significant difference (p < 0.05) appeared in scores for texture, taste and overall acceptability. Analysis by Tukey HSD test, further revealed that in scores for texture, taste and overall acceptability of stuffed parantha, significant differences (p < 0.05) appeared within 25 per cent and 30 per cent level of incorporation of sprouted pulses.For cutlets, the overall acceptability scores varied from 7.82±0.95 (Bengal gram cutlets) to 8.16±0.81 (Cow peas cutlets). In bengal gram and cowpea cutlets, significant difference (p < 0.05) appeared in scores for texture, taste and overall acceptability. Non-significant difference was obtained within all organoleptic characteristics of chick peas cutlets except for taste.

The best scores for overall acceptability for pulao varied from 8.04±0.96 (Cow peas pulao) to 8.33±0.89 (Bengal gram pulao). Significant difference (p < 0.05) was found in scores for taste and overall acceptability of pulao. Subsequent analysis of the data by Tukey HSD, indicated that significant difference (p < 0.05) was found only in taste scores for bengal gram pulao within 30 and 35 per cent while for cow peas pulao, significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed for taste and overall acceptability within 30 and 35 per cent. However, scores for all organoleptic characteristics of chick peas pulao were non–significantly different.

The overall acceptability scores awarded by the panel of judges for chat ranged from 8.10±0.62 (Cow peas chat) to 8.52±0.91 (Chick peas chat). At different level of incorporation that is, 35 per cent, 40 per cent and 45 per cent, non-significant difference was obtained within all organoleptic characteristics of Bengal gram chat except for overall acceptability. Further analysis by Tukey HSD test revealed significant difference (p < 0.05) for overall acceptability within 40 per cent and 45 per cent. However, in chick peas chat, significant difference (p < 0.05) was obtained within 40 per cent and 45 per cent level in scores for color. In cow peas chat, significant difference (p < 0.05) was noticed within 40 per cent and 45 per cent for taste only.

Statistical analysis for overall acceptability showed that judges were highly consistent in awarding the scores for chick peas dal curry (8.88±0.79), chick peas chat 8.52±0.91 ), bengal gram pulao (8.33±0.89 ), cow peas cutlets (8.16±0.81) and bengal gram stuffed parantha (8.10±1.07).

Estimation of Vitamin C Content in Cooked Pulses

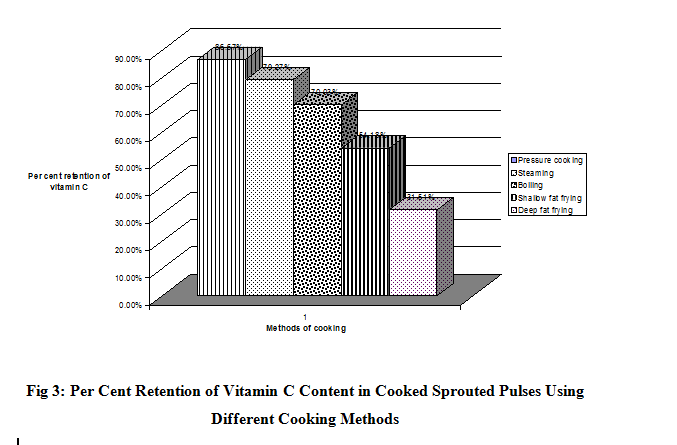

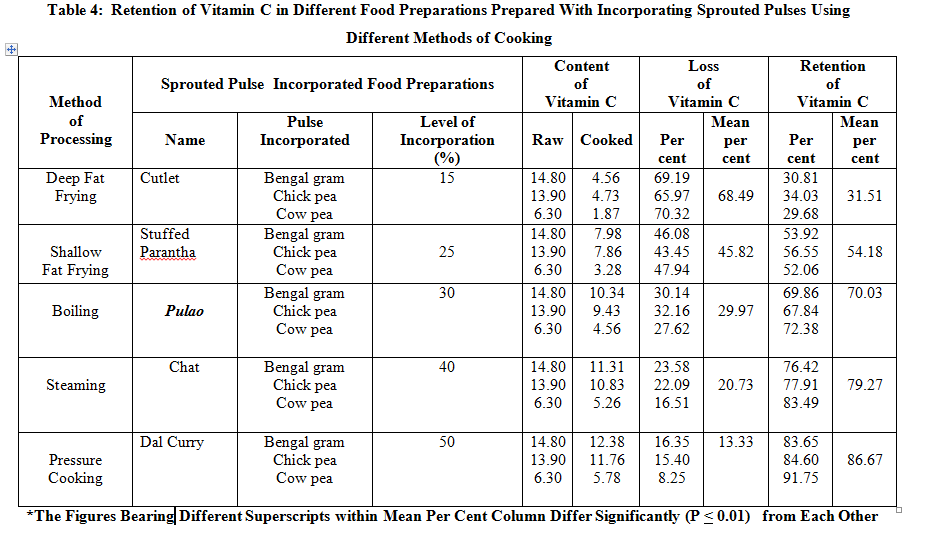

Table 4 shows that cooking had adverse effect on the retention of vitamin C content (Rahmann 1983). On cooking, vitamin C formed during sprouting is destroyed to a large extent, losses generally vary with the methods of cooking (Yadav and Sehgal 1995 & 1997, Kaur and Kochar 2005 & 2008). However, irrespective of the source of sprouted pulses incorporated for the preparation of different products, the values for the percentage retention of vitamin C from all the sprouted pulses within the same cooking method as well as in the same preparations were similar and the difference was also found to be

non - significant

Analysis of the data further revealed that significantly (P < 0.01) maximum retention of vitamin C was found in those preparations prepared by pressure cooking i.e. dal curry. The retention of vitamin C in these preparations varied from 83.65 (Bengal gram dal curry) to 91.75 (Cow peas dal curry) with mean per cent retention value of 86.67. In contrast to pressure cooking, the deep fat fried food preparations i.e., cutlets prepared by incorporating different sprouted pulses (Bengal gram, chick peas and cow peas), had retained significantly (P < 0.01) minimum amount of vitamin C content. The figures for the retention of vitamin C in cutlets ranged from 29.68 (Cow peas cutlets) to 34.03 per cent (Chick peas cutlets) with mean per cent retention of 31.51.

Intermediate content of vitamin C was retained in food preparations prepared by the methods of steaming (Sprouted bengal gram, chick peas and cow peas chat) followed by boiling (Sprouted bengal gram, chick peas and cow peas pulao) and shallow fat frying

( Sprouted bengal gram, chick peas and cow peas stuffed parantha) (Fig 3).

The per cent retention of vitamin C in steamed food preparations ranged from 76.42 (Bengal gram chat) to 83.49 per cent (Cow peas chat) with the mean per cent retention of 79.27 and in boiled food preparations, the figures varied from 67.84 ( Chick peas pulao) to 72.38 per cent ( Cow peas pulao) with average per cent retention value of 70.03. In shallow fat fried food preparations, the retention of vitamin C ranged from 52.06 (Cow pea stuffed parantha) to 56.55 per cent (Chick peas stuffed parantha) with mean per cent retention of 54.18. The findings of the present study are comparable with the reports of Abdel (1990), Kaur and Kochar (2005 & 2008), Mosha et al (1995),Nursal and Yucecan (2000), Rahmann (1983), Sood and Bhat (1974), Sood and Malhotra (2002).

Conclusions

Results of the present study revealed that cooking had a destructive effect on the vitamin C content. Pressure cooking was the method which resulted in least destruction or maximum retention of vitamin C, followed by steaming, boiling and shallow fat frying. Deep fat frying was the method which resulted in maximum destruction or minimum retention of vitamin C on cooking

References

Abdel-Kader ZM (1990) Studies on Some Water Soluble Vitamins Retention In Potatoes and Cowpeas as Affected by Thermal Processing and Storage. Nahrung 34(10): 899-904.

Achinewhu SC and Hart AD (1994) Effect of Processing and Storage on the Ascorbic Acid Content of Some Pineapple Varieties Grown in the Rivers of Nigeria. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr 46(4): 335-337.

Amerine MA, Pangborn RM and Roessler EB (1965) Principles of Sensory Evaluation of Food. New York: Academic Press.

Badshah (1992) Effect of Soaking, Germination and Autoclaving on Selected Nutrients of Rapeseed. Pak J of Scientific and Industrial Research 34(11):446-448.

Chattopadhyay H and Banerjee S (1953) Effect of Germination on Biological Value of Protein and Trypsin Inhibitor Activity of Common Indian Pulses. Ind. J. of Med. Res 41:185.

Gopalan C, Ramasastri BV and Balasubramanian SC (2000) Nutritive Value of Indian Foods, National Inst. of Nutrition, ICMR Hyderabad, India.

Kaur T (2009) Sensory Evaluation of Germinated Pulses Incorporated Food Preparations. A Report (unpublished) submitted to KUK.

Kaur T and Kochar GK (2005) Organoleptic Evaluation and Retention of Vitamin C In Commonly Consumed Food Preparations Using Underexploited Greens. The Ind. J. Nutr. Dietet 42 : 425.

Kaur T and Kochar GK (2008) Effect of Domestic Processing on the Retention of Vitamin C in Food Preparations Developed by Incorporating Sprouted Pulses. Research Reach 7(1):18-27.

Kavas A and Nehir ElS (1992) Changes in Nutritive Value of Lentils and Mung Beans During Germination. Food Engg. Dept., Engg. Univ. Turk.

Kuti JO, Kuti HO (1999) Proximate Composition and Mineral Content of Two Edible Species of Cnidoscolus (Tree Spinach). Plant Foods Hum. Nutr 53 (4): 275-83.

Mosha TC, Pace RD, Adeyeye S, Mtebe K, Laswaiti (1995) Proximate Composition and Mineral Content of Selected Tanzanian Vegetables and the Effect of Traditional Processing on the Retention of Ascorbic Acid, Riboflavin And Thiamine. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 48 (3): 235-45.

Nogueira JN, Soybine SJ, Vencosvsky R, Fonseca H (1978) Effect of Storage on The Levels of Ascorbic Acid and Beta Carotene in Freeze Dried Red Guava (Psidiu Guayava L.). Arch Latinoam Nutr 28 (4) : 363-77.

Nursal B and Yucecan S (2000) Vitamin C Losses in Some Frozen Vegetables due To Various Cooking Methods. Nahrung 44 (6) 451-53.

Rahmann A (1983) Effect of Cooking on Tryptophan, Basic Amino Acid, Protein Solubility and Retention of Some Vitamins in Two Varieties of Chick Pea. Food Chemistry, 11:139.

Sood M and Malhotra SR (2002) Effect of Processing and Cooking on Ascorbic Acid Content of Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L) Varieties. J. Sci. Agric 82 (1): 65-68.

Sood R and Bhat CM (1974) Changes in Ascorbic Acid and Beta Carotene Content of Green Leafy Vegetables on Cooking. J. Food Sci. Tecnol 11: 131-133.

Sundraraj DD and Thulasidas G (1980) The Botany of Field Crops. India: The Macmillan Co. Ltd.

Suzane K Gaby, Adrianne B, Vishnia NS, Lawrence JM (1991) Vitamin Intake and Health: A Scientific Review. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc: 108-134.

Vanderslice JT and Higgs DJ (1991) Vitamin C Content of Foods: Sample Variability. Am. J. Clin.Nutr 54 (Suppl) : 132-35.

Yadav SK and Sehgal S (1995) Effect of Home- Processing on Ascorbic Acid and Beta Carotene Content of Spinach (Spinach Oleracia) and Amaranth (Amaranthus Tricolor) Leaves. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr 47 (2) :125-311.

Yadav SK and Sehgal S (1997) Effect of Home- Processing and Storage on Ascorbic Acid and Beta Carotene Content of Bathua (Chenopodium Album) and Fenugreek (Trigonella Foenumgraecum) Leaves. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 50 (3) : 239-47.